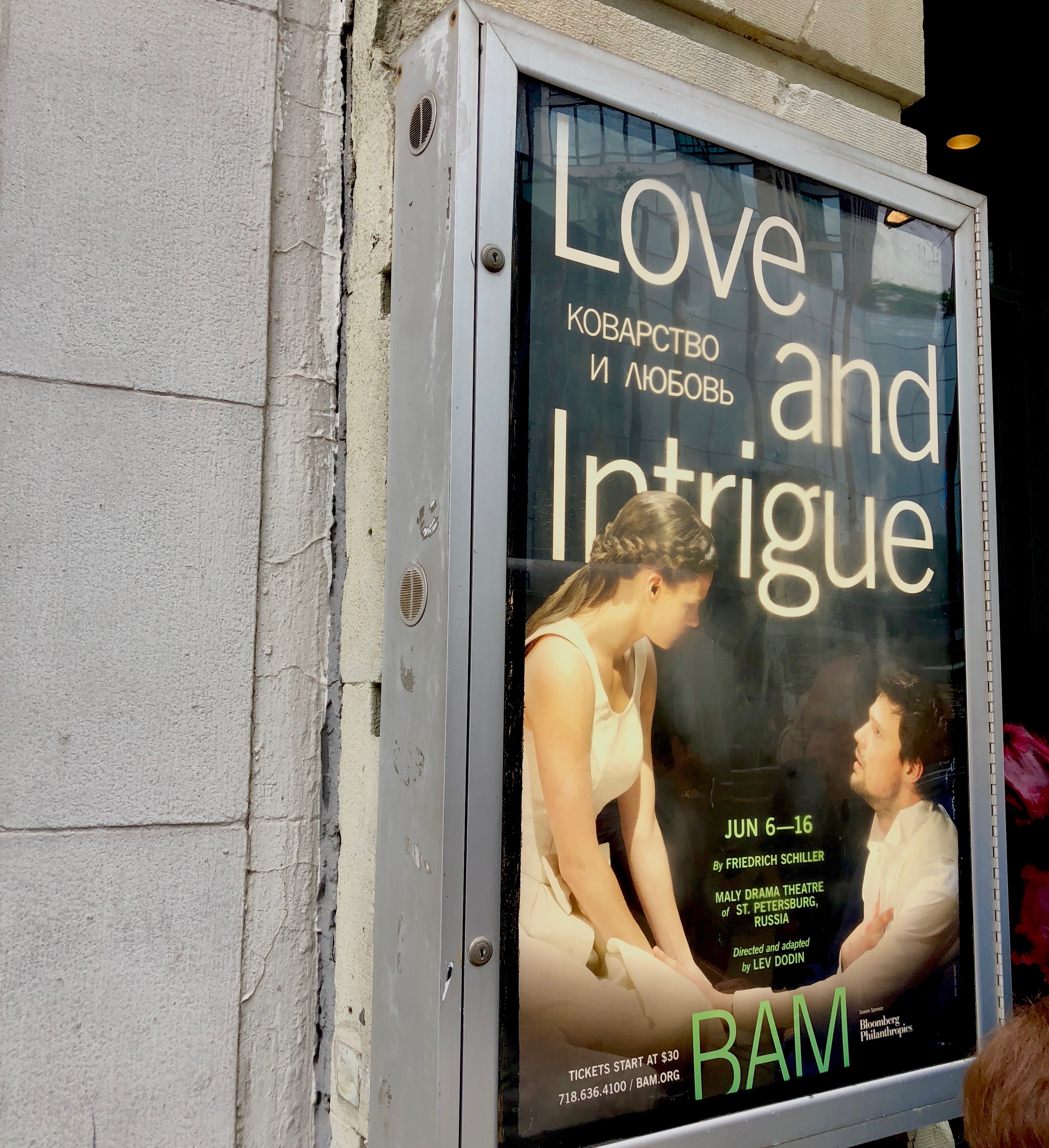

Friedrich Schiller, Love and Intrigue

The plot of this play in a nutshell: Someone has to marry someone to advance the interests of the state. But this first someone is in love with someone else. To protect itself, the state destroys that someone else, the first someone, and a bunch of others along the way. Eternal and international. Isn’t it?

Russian director Lev Dodin packed this German version of Romeo and Juliet — five acts on hundreds of pages — into two hours and a little bit, without an intermission. Not only was the text condensed to a minimum — the first several scenes became one long kiss — the whole concept was minimalistic. Costumes were black and white. The backdrop was a wooden cross (or a guillotine?) executed Kandinsky-Malevich style. The only decorations were seven tables strategically moved around the stage by a group of butlers and used as a dance floor, a place to read, write a letter, make love, perform a cross examination, celebrate.

This minimalism turned a lengthy romantic tragedy into a thriller zeroing in on eternal and international conflicts: parents and children, nobility and simple folk, dignity and treachery, state and person.

The language was not archaic but it was a language that is now unfortunately becoming extinct: choice of words, full sentences, structure of phrases, pauses. Listening to actors was like drinking.

And the actors really felt what they were performing and did that following the style of the play. Even more so — they were aware of each other. It was an ensemble where one felt the elbow on another. Is that what they call chemistry? The most memorable was of course Lady Milford (Ksenia Rappoport) — her movements, her suave, emotional shifts…

How clever and breathtaking the final scene was! Seven large dark wooden tables arranged in a quad on the dark stage were covered with piercingly white tablecloths. On top, each one had a large candelabra, a carafe with a ruby red liquid, and a glass vase with white tulips. As passions were tearing the front of the stage apart in rapid succession, meticulous and slow table set up by butlers in the background was mesmerizing. Slow and fast, dark and bright, loud and quiet, colorful and monochrome, passionate and content — all at the same time, in one small space, in one brief moment.

Now, the dead body of Louise Miller was on the front table in a pool of that red lemonade in which Ferdinand mixed arsenic to poison her. Ferdinand’s body was on the chair in front of another table — two lovers killed by intrigues and treachery of others. Meanwhile, behind them, among that magnificent setup, an important state wedding or inauguration was taking place. Over the music, over the festivities, over the dead bodies, the voiceover was reading Bismarck’s letter. Was it a toast, a greeting?

“For a politician, the most important task that precedes the rest is to equip his national, state, and human home. Others can easily endear us with love — maybe too easy — but not with threats, not with blind resistance, not with rejection. We are afraid of God, God alone, and no one else. And our fear of God makes us love, preserve, and improve the world. “

As they heard this, dead raised their heads.

Feels like now. No?